What the Hell is That Smell?

by Kristen Pumphrey

Welcome to What the Hell Is That Smell? A new series where we talk about specific fragrances, where they originate from, and how they are used in perfumery today.

Let’s dive into some fragrance terminology and explore a popular perfume compound, musk. Musk is incredibly prevalent in perfumery and gives fragrances depth and body. Musk is considered a base note. Molecularly speaking, bases are very heavy stable compounds and dissipate much more slowly than mid or top notes. Musk notes will linger in the air, great for creating long lasting fragrance in your home.

The history of musk begins with natural musks that were derived from animals like the musk deer. The scent was used to attract partners among other deer — which explains why it evokes such visceral reactions in perfumery today. Extracting these musks was cruel to animals, because typically the animal was killed in order to obtain the musk. Because of this practice, musk became an incredibly expensive ingredient. Ethical considerations, as well as cost, lead to the widespread adaptation of synthetic musks which are now used almost exclusively.

So, how would you describe musk? Musk is incredibly versatile because it can give an animalic, intimate scent or it can smell clean and fresh. Musks are almost always soft and add a rounded texture, and are not just in heavy, sexy scents. It’s also an important fragrance constituent in laundry detergent as it imparts that clean, freshly washed linen smell. Because of how heavy and stable the compound is, the scent of musk lingers for a long time on clothing (a form meets function of long-lasting detergent scent as well as the fragrance component itself). Many people’s first interaction with musk was likely The Body Shop’s white musk (I personally remember using it one summer to remind me of my long-distance boyfriend.)

Time for some technical perfumery: Musk molecules that are heavy and a little sexy (and mimic an animal) would be muscone and ambroxide. White musk molecules that are soft and clean would be glaxoile and ambrettolide. Ambrette seed and angelica root are examples of a natural vegetable musk.

Because musks can be so versatile depending on which molecule you use, I like to think of musks as imparting body and texture to a scent. They blend beautifully with warm skin as well, which is why they’re so popular in perfumery. A fun fact about musk is that many, many people (maybe even 50% of the population) are actually anosmic to it, meaning they can’t smell it. If you think about musk as a texture instead of just the fragrance, it’s easy to train yourself to begin to smell it.

Tom and I took a perfumery class here in Los Angeles at the Institute of Art and Olfaction, and the instructor set up a “blind smell test” — one fragrance tester strip dipped in musk, and two dipped in nothing. She asked which one was different and instructed him to look for the texture (the way the scent felt in his head and body) vs the smell. He could differentiate between the strips — which meant that his nose could be trained to smell musk after all. Now, Tom says he looks for the texture and almost an absence of a fragrance when identifying a musk in a candle.

P.F. fragrances that have musk in them are Teakwood & Tobacco, Sweet Grapefruit, Amber & Moss, Sandalwood Rose, Los Angeles, Golden Hour, and Moonrise.

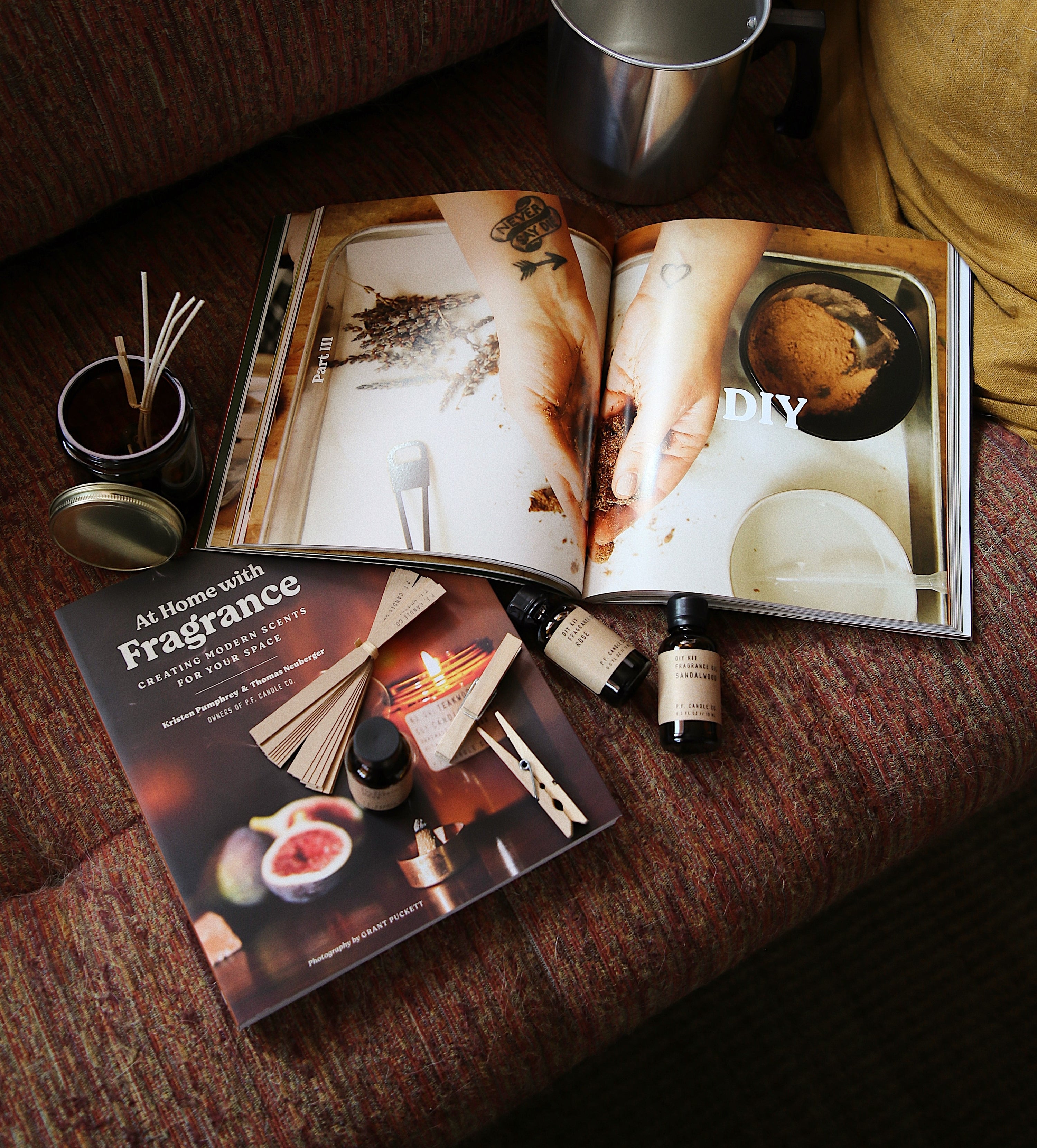

If you liked doing a deep dive on musk, check out At Home with Fragrance for more easily digestible fragrance information!

Let’s dive into some fragrance terminology and explore a popular perfume compound, musk. Musk is incredibly prevalent in perfumery and gives fragrances depth and body. Musk is considered a base note. Molecularly speaking, bases are very heavy stable compounds and dissipate much more slowly than mid or top notes. Musk notes will linger in the air, great for creating long lasting fragrance in your home.

The history of musk begins with natural musks that were derived from animals like the musk deer. The scent was used to attract partners among other deer — which explains why it evokes such visceral reactions in perfumery today. Extracting these musks was cruel to animals, because typically the animal was killed in order to obtain the musk. Because of this practice, musk became an incredibly expensive ingredient. Ethical considerations, as well as cost, lead to the widespread adaptation of synthetic musks which are now used almost exclusively.

So, how would you describe musk? Musk is incredibly versatile because it can give an animalic, intimate scent or it can smell clean and fresh. Musks are almost always soft and add a rounded texture, and are not just in heavy, sexy scents. It’s also an important fragrance constituent in laundry detergent as it imparts that clean, freshly washed linen smell. Because of how heavy and stable the compound is, the scent of musk lingers for a long time on clothing (a form meets function of long-lasting detergent scent as well as the fragrance component itself). Many people’s first interaction with musk was likely The Body Shop’s white musk (I personally remember using it one summer to remind me of my long-distance boyfriend.)

Time for some technical perfumery: Musk molecules that are heavy and a little sexy (and mimic an animal) would be muscone and ambroxide. White musk molecules that are soft and clean would be glaxoile and ambrettolide. Ambrette seed and angelica root are examples of a natural vegetable musk.

Because musks can be so versatile depending on which molecule you use, I like to think of musks as imparting body and texture to a scent. They blend beautifully with warm skin as well, which is why they’re so popular in perfumery. A fun fact about musk is that many, many people (maybe even 50% of the population) are actually anosmic to it, meaning they can’t smell it. If you think about musk as a texture instead of just the fragrance, it’s easy to train yourself to begin to smell it.

Tom and I took a perfumery class here in Los Angeles at the Institute of Art and Olfaction, and the instructor set up a “blind smell test” — one fragrance tester strip dipped in musk, and two dipped in nothing. She asked which one was different and instructed him to look for the texture (the way the scent felt in his head and body) vs the smell. He could differentiate between the strips — which meant that his nose could be trained to smell musk after all. Now, Tom says he looks for the texture and almost an absence of a fragrance when identifying a musk in a candle.

P.F. fragrances that have musk in them are Teakwood & Tobacco, Sweet Grapefruit, Amber & Moss, Sandalwood Rose, Los Angeles, Golden Hour, and Moonrise.

If you liked doing a deep dive on musk, check out At Home with Fragrance for more easily digestible fragrance information!